Guest Blog: Andrew Mitchell, Senior Advisor to Ecosphere+, discusses why COVID-19 is a symptom of environmental degradation and wildlife crime, and argues that it’s time for the finance sector to take stock of the global economy’s dependence on biodiversity.

This blog was initially featured on Equilibrium Futures.

A letter to the World Health Organisation this week, signed by almost 250 environmental organisations, points to a solution to prevent future Corona virus outbreaks – a massive crackdown on wildlife trade markets worldwide. But will banks, insurers and investors begin to recognise this health crisis for what it is – a symptom of a US$ trillion trade in environmental degradation and wildlife crime. C-19 demonstrates that it is time for the financial sector to think “beyond carbon,” and put nature-related impacts and dependencies firmly onto their risk map. Here’s why.

Economists estimate the economic fallout from the COVID-19 virus pandemic could approach $10 trillion dollars, or around one eighth of global GDP. To prevent a recurrence of this crisis, we need to look less into human health, than into the collective blindness among regulators and within the financial sector of the huge dependencies the global economy has on biodiversity, and the devastating impacts on us all when our effect on these dependencies, becomes increasingly unsustainable. COVID-19 is nature’s $10 trillion bite back, and this is just the beginning.

The World Economic Forum’s January report ‘Nature Risk Rising’ acutely charts the financial risks of messing with nature. Its January Global Risks report placed biodiversity as the 3rd highest future risk for business impact in 2020. At the Forum in Davos this January, I found few in the financial sector taking the issue of biodiversity risk seriously. With financial markets plunging and lenders struggling to keep the economy moving, many are now asking how could this happen? An understanding of how and why an invisible microbe that lives harmlessly in wild animals has gone viral, threatening us all, may help avoid such an attack on humanity but also it can encourage asset owners to create a new policy to ‘do no harm’ to nature.

Zoonoses is a term used by biologists to describe reservoirs of pathogens normally living in domestic livestock and wild animal populations, that very rarely can transfer to humans. Examples include Ebola, HIV, and Leptospirosis. For such a zoonotic transfer to occur, an intensive situation needs to be created with a high concentration of the primed pathogen and humans in close and often bloody proximity. Poorly managed wildlife markets provide the perfect conditions for the necessary transfer and mutations to occur, and none better than in China. Here bats, snakes, and pangolins are served up in a daily blood bath alongside every other imaginable creature, many illegally sourced from across the world.

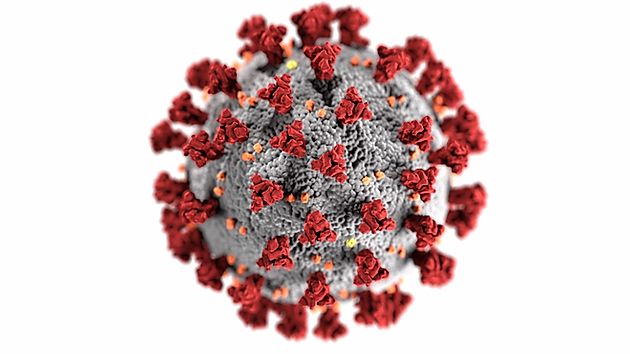

SARS-CoV-2, the source of the COVID-19 pandemic, is a form of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome and the 7th coronavirus known to infect humans. These viruses are common in bats and have been transferred to humans before, possibly mutating through camels in the Middle East, as MERS. A more transmittable form, popularly known then as SARS, first broke out of the Chinese wildlife markets in 2002, infecting at least 8000 humans across 29 countries. The 2019 version is far more potent. At the time of writing confirmed infections are rising over 1.2 million, with more than 70,000 deaths recorded across 208 countries. The Corona viral cat is now well and truly out of the pangolin bag.

So how are bats or pangolins involved and why did the jump occur now? For thousands of years, pangolins, scaly anteaters with prehensile tails, have roamed the forests of South East Asia and Africa, mostly preyed upon by leopards, lions and tigers. In the 1980’s and 90’s when increasing human populations and unsustainable investments in agriculture delivered deforestation, this brought a growing supply of illegal bush meat to increasingly prosperous city markets. As prosperity grew in China and Asia generally, traders to the wildlife markets of Wuhan, and many other cities spread across the region, began to take an interest. In the last decade the covert supply chain into these markets has delivered up to 100,000 pangolins a year, making it the most illegally traded mammal in the world. Pangolin parts in black markets can reach US$3000 per kilo for their scales; a kilo of meat fetches $300. Their scales, equivalent to our fingernails, are touted as medicine. This is not a trade for the poor, but the rich.

The armoured nature of pangolins and their ability to curl up into a defensive ball, makes them ideal to conceal in a box. Terrified, weakened, and infecting each other, they are transported thousands of miles away from their homes, to China. Here they disgorge millions of primed Corona viruses around wildlife market butcheries also serving up bats. The vast Huanan ‘wet’ market in Wuhan is not all bad. It serves thousands of people their daily fish, fruit and veg. But the meat section is extraordinary. The Corona virus was first found to be prevalent where wild animal parts are sold, not in the rest of the market.

Corona viruses are highly adaptable microbes and dense populations of humans, without antibodies to combat them, eventually make ideal testing grounds. Dr Li Wenliang, a 34-year-old ophthalmologist in Wuhan, along with 7 other colleagues, first alerted the Chinese public to the threat last November. Following, a reprimand from Chinese police for spreading “false rumours,” he later died of the virus.

So can science prove the link? In recent months, several laboratories have investigated the deadly Corona virus genome in humans. The nucleic acid sequences sampled from animal viruses found in the genus Rhinolophus, or horsehoe bats, offer a good match. One strain, known as RaTG13, from a cave in Yunnan, in SW China, has a 96% match with SARS-CoV2, the correct name of the virus. Bats are probably the reservoir; but some differences with the human Covid virus, suggests modification via another animal. What indicates the pangolin, as a potential source or intermediary, is that it’s Corona virus has an especially good ability to bind onto human cells, which the bat version lacks. Such intermediaries, might pre-dispose the virus to make its jump to humans. The earlier SARS strain, also from bats, had a 99.8% match with one found in civet cats, another illegally traded species in Chinese markets. Only an unnatural cocktail that brings all of these wildlife elements together, alongside humans, can turbocharge the conditions needed for multiple mutations to take place, one of which eventually outfoxes our immunity – and so the virus explodes.

Could the virus have been constructed by humans and then escape from a laboratory? Both the American Military and the Institute of Virology in Wuhan have been accused in the media. The science says no. Highly skilled lab technicians manipulating viruses, are not nearly as adept as nature is at re-designing them. Technicians usually leave a lab-based backbone of chemical footprints. None of these have been found in the human version of C-19.

Humans may not have created the corona virus, but we have cultured the un-natural conditions needed for nature to detonate a $10 trillion time bomb into our economy. The cost of preventing the economic impact, to say nothing of the damage to families, would have been small. China has at last acted to shut down wildlife markets across the country,15 years late. Might this week’s letter to WHO stimulate more comprehensive global action? China is by no means alone in harbouring such markets.

Degradation of nature and the scale of environmental crime, plus the laundering of its proceeds, is far greater than the wildlife market trade alone. Last year’s Refinitiv report on financial crime values illegal wildlife tracking at between US$15-23bn a year, making it the 4th largest illegal trade behind drugs. A 2016 UNEP-Europol report estimated direct environmental crime including logging, fishing and mining to be US$90-260bn per year. A 2019 World Bank report estimates the full costs of environmental crime including the loss of ecosystem services upon which the economy depends, to be in the range of US$1-2 trillion per year globally. 90% of the costs were from illegal deforestation and fishing.

Corona is an acute reminder of the consequences coming the financial sector’s way, if humanity continues to mess with nature. It should be a wakeup call to banks insurers, investors and business, that the ‘E’ of ESG should not be confined to carbon. A Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosure (TNFD) is in the works, as a follow on to the TCFD. The time to do this is now because: Nature-related risk affects many sectors; can be bigger than carbon risk; and can take a bite out of our economy faster than climate. Nature-related risk cannot wait, whilst we fix climate risk.

As I write, my dear friend Robin Hanbury-Tenison, explorer and Chairman of Survival International, is in a coma fighting C-19. Ironically, the first Chapter of his book, ‘Taming the Four Horsemen’, released a few months ago before the outbreak engulfed Europe, is called: The Problem: Pandemics. To keep the White Horseman of pestilence at bay, it is time our economy re-invented itself to maintain Earth’s immune system, and not to degrade it.

Andrew is the Founding Director of the Global Canopy Programme, an environmental think tank based in Oxford and is Senior Advisor to Ecosphere+. He is an international thought leader on tropical forests and climate change, with extensive field experience in Asia, Africa and Latin America, and has 40 years of experience at the frontline of conservation policy in developing countries.

At Ecosphere+, we work with businesses large and small to develop natural climate solutions that mitigate climate change and prevent deforestation. Our clients are protecting threatened forests and highly valuable ecosystems around the world through investing in conservation and community regeneration projects. This is not only essential in the fight against climate change, but is key to mitigating nature-related risk, such as from virus causing pathogens, by reducing human encroachment into natural ecosystems.