The global carbon offsetting scheme reached by the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) in October 2016 is a highly commendable achievement that provides a starting point to drive change in the aviation industry over the coming decades. The deal is not without its detractors from within the environmental community but it does provide an unprecedented opportunity to save threatened forests and significantly narrow the existing emissions gap for achieving a safer climate. The rules for offsets under the ICAO Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) scheme are under development, including the types of offsets that will be accepted. Forest carbon offsets can offer the most effective climate solution the world has today to materially reduce emissions, and is easily understood by consumers.

These offsets can also supply the volume that the aviation industry needs to meet its emission reduction targets at reasonable costs with environmental integrity as well as a multitude of additional benefits, including poverty alleviation, biodiversity conservation and improved water and food security. This provides the airline sector with the ability to deliver a material climate change solution as well as contribute to wider United Nations sustainable development goals that can only strengthen CORSIA.

At COP21 in Paris, 195 governments agreed the ambitious goal of “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels”. This is what is necessary to keep our climate within ‘safe’ limits, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 5th Assessment report. While the governments of nearly every country on earth have made ambitious pledges to cut emissions, there is still a significant gap in what’s needed.

In order to achieve holding global temperature rise to no more than 2°C, the world must reduce an additional 12-17 GtCO2e by 2030 on top of the country climate commitments made in Paris, according to the UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2016. This ‘emissions gap’ makes clear that significant action from the private sector is needed. By agreeing CORSIA, the aviation industry has taken steps towards curbing emissions from international aviation and playing its part in closing the emissions gap, despite the sector not being mentioned in the Paris Agreement.

THE POTENTIAL OF FORESTS

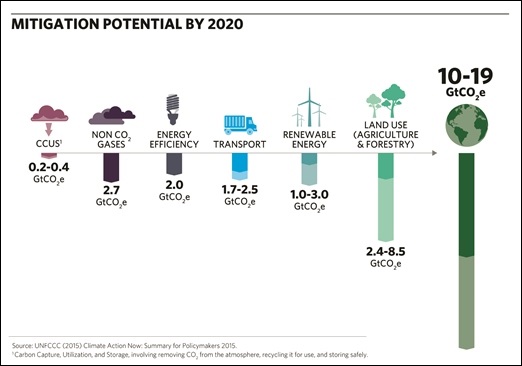

Sustainable land use, which includes agriculture and forestry, could deliver about one third of the required near-term emission reductions that are required. It will be impossible to limit global temperature rise to no more than 2°C without stopping the current dramatic deforestation and degradation of forests as well as transforming unsustainable forestry and agricultural practices. Halting deforestation is the largest and most cost-effective immediate opportunity to reduce global emissions.

Photosynthesis, the natural process of plants taking in CO2 and releasing oxygen to make their own food, is the oldest technology in the world. And it is available today without the need for years of expensive research or engineering experimentation; it just needs the right focus. To realise this potential, one key ingredient is missing: a value on forests left standing, a reason to keep trees in the ground. Whilst this sector has enormous potential in terms of climate change mitigation and sustainable development, it only receives around 5% of public climate finance and does not benefit from strong policies in the way the energy sector does. This makes the private sector critical. The airline industry could provide the necessary demand and investment to make significant headway. Surely this opportunity cannot be ignored? Once the forests are gone, it is likely forever, and the remaining carbon budget yet more challenging.

In terms of volume, as shown in the figure below, emissions reductions from land use, which includes agriculture and forestry, have the potential to mitigate a massive 2.4 – 8.5 GtCO2e, with a further 12 GtCO2e possible by 2030.

THE AIRLINE DEMAND FOR OFFSETS

The demand for offsets from CORSIA is substantive. It is estimated by ICAO that airlines will generate an offset demand of 288 to 376 MtCO2e/year by 2030. By comparison, the volume of offsets used in the EU ETS averaged approximately 202 MtCO2e over the period 2008-2012, according to analysis by the European Commission. So from a standing start, airlines will need access to offsets very quickly. At the same time, demand for offsets is also increasing from other sectors as countries implement their Paris commitments.

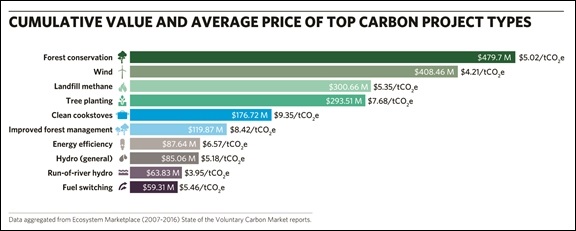

Forest carbon has the capacity to provide a high quality volume of offsets to address this demand. As the figure below shows, forest conservation is also one of the most cost-effective types of carbon offsets, behind only wind and run-of-river hydropower, and has the largest volume transacted within the existing voluntary carbon markets. The evidence is clear that forest carbon offsets have huge potential to meet the coming demand for offsets from CORSIA at a competitive price.

High quality forest carbon offsets are a well-established approach to achieving emissions reductions. But that isn’t all. Forests provide a host of additional benefits to ecosystems and communities around the world – beyond climate goals.

Forest carbon offsets offer real carbon mitigation and their inclusion in the Paris Agreement puts an official stamp of approval on them. The climate deal represents an internationally negotiated and agreed-upon framework for sustainable land use management and forest conservation. Governments worldwide recognise forests as an effective climate mitigation strategy, and land use was included in 119 of the 162 carbon mitigation plans submitted by countries as part of the agreement.

The ICAO Assembly resolution that established CORSIA explicitly recognised the tools for mitigating emissions included in the Paris Agreement, such as REDD+ and the existing Clean Development Mechanism, a previous UN initiative through which countries purchase emissions reductions from developing countries. Additionally, these offsets will need to meet the ‘emission unit criteria’ that is currently being developed by ICAO.

Forest conservation projects that deliver clear carbon benefits have come a long way in the last two decades and there are now well-practiced and robust methods for ensuring emissions savings are permanent. For example, projects first perform detailed risk assessments to understand the threats to the forest. Secondly, a buffer system is introduced that acts like an insurance mechanism. If forest land is then found to be lost (as part of the intensive monitoring process), the corresponding number of offsets in this buffer are retired, meaning they are never placed on the market, ensuring the integrity of the offsets that are finally issued.

Stringent standards also put safeguards in place to prevent leakage, which in this case means the risk that deforestation is moved outside a project area, similar to the threat that refineries and other energy intensive industries would move outside of Europe once the EU ETS came along. To avoid and account for this in forest conservation projects, a detailed risk assessment informs a leakage mitigation strategy. The risk areas are then monitored and any leakage is deducted from the emissions performance of the project. Countries are also working on national and jurisdictional level systems to account for every tonne of forest carbon; in time bottom-up projects can ‘nest’ into these top-down systems.

Amazonian rainforest in the Cordillera Azul project in Peru, protected through forest carbon finance by Ecosphere+

Beyond carbon benefits, forest carbon projects also deliver a range of other environmental and social benefits, often referred to as co-benefits, especially when compared to carbon reductions in other sectors such as land-fill gas management. These include protecting biodiversity-rich primary forest, creating sustainable livelihoods for impoverished local communities, providing climate resilience to sustainably produced crops, as well as a range of ecosystem services such as mitigating flooding, reducing soil erosion and conserving water resources. For example, UNEP estimates tropical forests provide food, water, fuel and medicine to 1.6 billion people. Because of this, forest carbon projects are one of the most volume transacted offset types on the voluntary carbon market.

It is also for these reasons that forests are easy to explain to the public, including airline passengers, as a worthwhile activity for airlines to invest in. They have already featured in voluntary airline offset schemes, including those run by Delta and Qantas, as well as other voluntary schemes such as BP’s Target Neutral.

ENSURING HIGH QUALITY

Not all offset projects are created equally. Over the years, a handful of poorly designed and executed forest carbon and other projects have had negative impacts on their local people and environment and, rightfully, have received a bad press. However, these are not representative of common practice. They do not prove that saving forests is not a climate solution that brings sustainable development to local communities and protects a host of critical environmental services.

It is standard for forest carbon offset project developers to verify the emissions reductions and additional benefits through independent third parties. The Verified Carbon Standard and the Climate Community and Biodiversity Alliance are leaders on carbon accounting and co-benefits respectively. They have detailed and sophisticated requirements to ensure that projects certified by them have lasting benefits and maintain environmental integrity.

ICAO is working to define the types of offsets that will be accepted as part of the emission unit criteria and what can be used for ‘early action’. The rules for early action should provide further certainty next year on offset vintages and project types that will enable airlines to start investing in offsets. Carbon offsets for CORSIA must come from reliable, well-established, cost-efficient sources in order for ICAO to be successful in meeting the scheme’s climate targets.

It is clear that forests offer an opportunity for the aviation industry in many respects; they are well-positioned and immediately available to fulfil the demand; and are a real win-win for companies, society and the planet.

This article was originally written for GreenAir Online, as an opinion piece. GreenAir Online is the leading independent reporting online publication on aviation and the environment.